U.S. Supreme Court, in 7-2 Decision, Finds Andy Warhol’s Prince Portraits Not Transformative

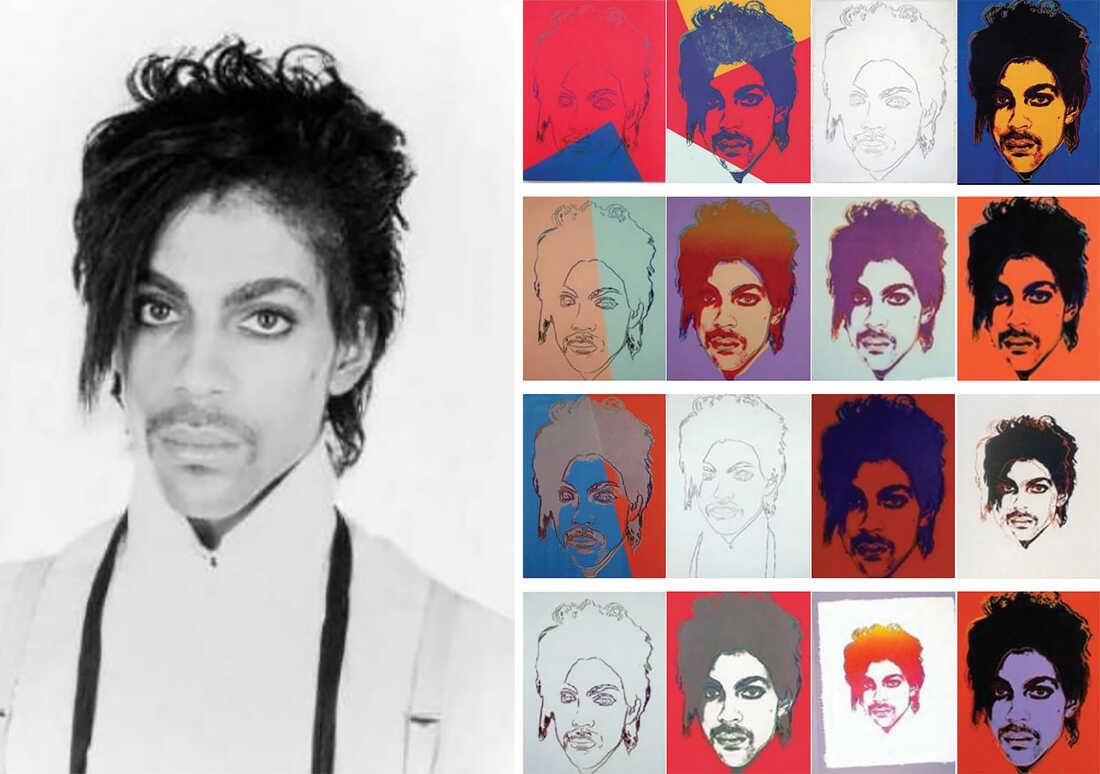

On Thursday, May 18, the Supreme Court issued its long-awaited decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith. This case centers on a photograph of the musical artist Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith in 1981. In 1984, the famous artist Andy Warhol, under a limited, “one-time” license from Goldsmith, used the photograph as the basis for a silkscreen portrait of Prince, which appeared in Vanity Fair. Unbeknownst to Goldsmith, however, Warhol also created additional silkscreen portraits from the photograph, and later, after Warhol’s death, his namesake foundation (AWF) licensed those additional portraits to others for payments in the thousands of dollars. In particular, a version of the portrait known as Orange Prince was reprinted in a magazine commemorating Prince’s death in 2016.

Photo: NPR, “The Supreme Court meets Andy Warhol, Prince and a case that could threaten creativity” (Oct. 12, 2022)

Goldsmith complained that the additional portraits were not licensed and infringed her copyright in the original photograph. AWF defended on the ground that Warhol’s use of the photograph to create the portrait was a “fair use” under copyright law. Under copyright law, “fair use” is evaluated under several factors; in this case, the Supreme Court was called on to decide just one of these factors, namely, “the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for non-profit educational purposes.” In earlier Supreme Court cases, the Court has evaluated this first factor by determining whether the use was “transformative,” i.e. whether and to what extent the use at issue has a purpose or character different from the original.

In addressing that question here, the Court, through a 7-2 majority opinion by Justice Sotomayor, held that the particular use at issue was not a transformative use and that this factor therefore weighed against AWF’s position. Although AWF argued that Warhol’s portrait conveyed a different message than did the original photograph (for example, presenting Prince as an iconic figure rather than a more realistic individual) the Court held that, even if so, this one fact did not conclusively establish that the use was “transformative” – otherwise, such a finding would swallow a copyright owner’s right to creative derivative works themselves, the statutory provision for which expressly states that a derivative work may be one that “transform[s]” the original.

Instead, the Court focused on the particular use at issue – AWF’s commercial licensing of the portraits for payment – and concluded that this use was not transformative. Specifically, the Court held that the purpose of the use of Orange Prince in 2016 was to illustrate a magazine article about Prince following his death, and that any difference between the message conveyed by the portrait and the message that would have been conveyed by the original photograph was not sufficient to render AWF’s use “transformative.” Therefore the Court concluded that the first factor of the fair use test did not favor AWF and remanded the case to the Second Circuit for further proceedings.

In a lengthy dissent joined by Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Kagan took issue with “the majority’s lack of appreciation for the way [Warhol’s] works differ in both aesthetics and message from the original templates” and described Warhol as “the avatar of transformative copying,” citing works such as his iconic Marilyn Monroe silkscreen. The dissent also discussed the long tradition of inspiration in the literary, visual and musical arts.

One way to interpret these two very different opinions is to note that the dissent focuses on whether Warhol’s creation of the Prince portraits was a transformative fair use, whereas the majority focuses on whether AWF’s commercial licensing of the portraits was transformative. As the impact from this opinion is felt in future cases, therefore, it is likely that, depending on their position, litigants will want to take into account just what the use at issue is. Given the disparity between the two views in this case, there is certain to be much development of these themes in copyright litigation going forward. Please contact your Vorys attorney with any questions about this fascinating and important development.

The Court also issued its decision in Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi on May 18. We will release a client alert on the implications of that decision early next week.